Opioid overdose deaths in D.C. reached a record high last year amid a nationwide surge in drug deaths, according to District data.

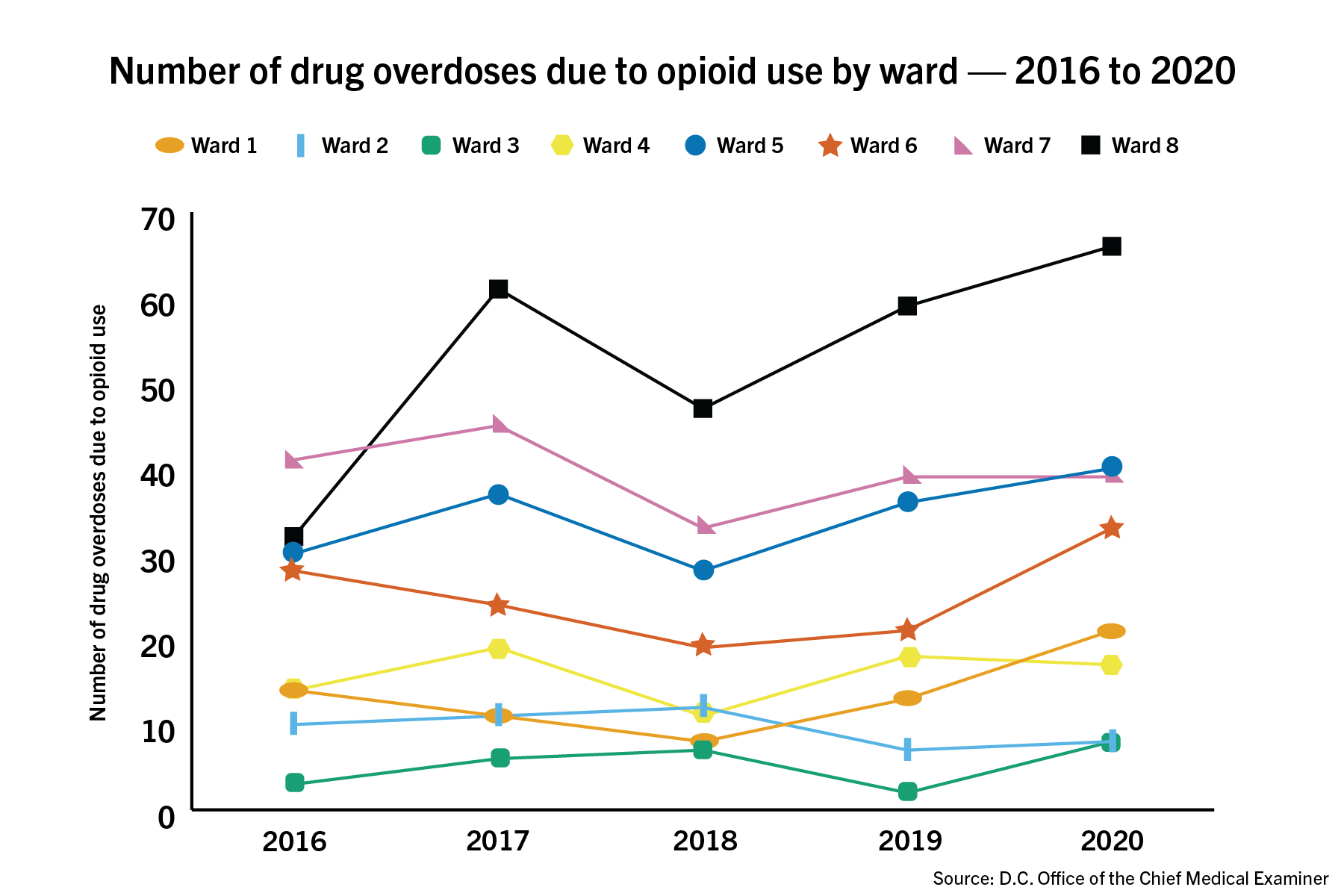

Data released by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner last month showed that Ward 2, where GW is located, sustained only eight opioid deaths over the course of the year, compared to 39 and 66 deaths in Wards 7 and 8, respectively. Experts in opioid addiction said the COVID-19 pandemic has created conditions of stress and isolation, exacerbating a crisis that has been growing for several years.

Sidney Lee | Graphics Editor

The data show that the 349 overdose deaths in the first 10 months of the year had already surpassed the previous yearly record, set in 2019 at 281 deaths, by 24 percent. The data show that in 2020, there were 34.9 deaths per month, an almost 50 percent increase from the 23.4 deaths per month in 2019.

Mayor Muriel Bowser vowed in 2018 to cut opioid deaths in half by late 2020. The D.C. Council approved legislation in December that broadened the number of D.C. government employees approved to carry naloxone, a drug overdose antidote, and expanded “Good Samaritan” laws, which provide legal protections to people who report overdoses to 911.

“We are confronting so many crises all at the same time,” Ward 6 D.C. Council member Charles Allen told The Washington Post in December. “There’s a really strong sense of urgency to continue the work of reducing opioid deaths.”

Tarlise Townsend, a postdoctoral fellow at the New York University School of Medicine and an expert in drug epidemiology and policy, said the COVID-19 pandemic has likely worsened the opioid epidemic. She said the added stress people have experienced as a result of the pandemic has likely increased the use of fentanyl, an opioid that is “more potent than heroin” and was involved in 94 percent of D.C. opioid deaths in 2020.

“One hypothesis is that this mental and emotional toll that COVID is taking on us is leading people to use drugs more frequently and more intensely, and that could be contributing to overdoses,” Townsend said.

Wards 2 and 3 have sustained the lowest number of deaths since at least 2016, both logging eight deaths during the first 10 months of last year, according to the data. Every other ward has tracked more than 20 opioid deaths over the course of last year.

The report also showed that opioid deaths disproportionately affected Black residents, accounting for 85 percent of total deaths citywide last year despite making up only 44 percent of the population. Townsend said these “alarming trends” still need to be studied, but continued “racist policing and racist drug war policies” play a role in creating those disparities.

She said the “Good Samaritan” approach to addressing overdosing can be difficult to implement in communities with low levels of trust in the police.

“We have deep-seated institutional and individual racism that pervades our drug war, our drug policy and our broader societal situation, and that’s going to interact with the policies that we create,” Townsend said. “We need to really tackle disparities at their roots and be very intentional about tackling them in our overdose policy responses.”

Townsend said local and federal policymakers must make changes to stop what is now a yearslong increase in drug deaths nationwide, including increased access to safe syringes and dependence-relieving drugs like buprenorphine for those who suffer from addiction.

She said while drug decriminalization laws, like recent legislation in Oregon decriminalizing the possession of all drugs, still need to be studied, there needs to be a “serious conversation” in the country about whether they could potentially be better at preventing overdose deaths than strict drug laws.

“We need to be thinking hard about whether the resources that we’re allocating to the criminalization of drugs is really producing our best possible outcomes,” Townsend said.

District officials have taken steps over the past few years to address the opioid epidemic, including when officials decriminalized the possession of drug paraphernalia in December and expanded access to overdose-reversing drugs like Naloxone.

Courtney Hunter, the vice president of state policy at the Connecticut-based anti-addiction organization Shatterproof, said COVID-19 restrictions have created limited access to inpatient addiction treatment, causing increases in drug overdoses and deaths. Hunter said mental health issues caused by social isolation and financial uncertainty have contributed to the increase in drug use, as well as decreased use of substance abuse recovery programs in D.C.

D.C. health care providers have previously been more limited in their ability to administer the dependency-relieving drug buprenorphine because of the X-waiver requirement, which required providers under the Controlled Substance Act to complete eight hours of training being able to administer the drug.

The Department of Health and Human Services eliminated the X-waiver requirement for physicians treating up to 30 patients at a time last month, which Hunter said would increase access to the drug.

She said officials on the local and federal levels need to implement long-term reforms to decrease opioid deaths, like creating a greater public awareness of the opioid epidemic.

“Educate the public and specific populations like health care professionals with evidence-based information on addiction,” Hunter said. “Medical education on addiction is sorely lacking in medical schools.”

Silvia Martins, an associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University, said improving access to health care for medically underserved residents could lead to a decrease in opioid deaths among marginalized populations.

“It’s mainly affecting more vulnerable populations, populations that don’t have access to adequate resources and health care opportunities,” she said. “The relief, stable housing and also access to unemployment insurance and access to social services would help mitigate opioid overdoses.”

She added that social and economic stress caused by the pandemic have likely caused the spike in drug-related deaths.

“Social and economic hardship can lead to psychological distress that can then lead to increased drug use which can lead to overdoses,” Martins said. “In addition, people will have less financial resources to access adequate treatment, including counseling and medication if they need treatment for drug use problems.”